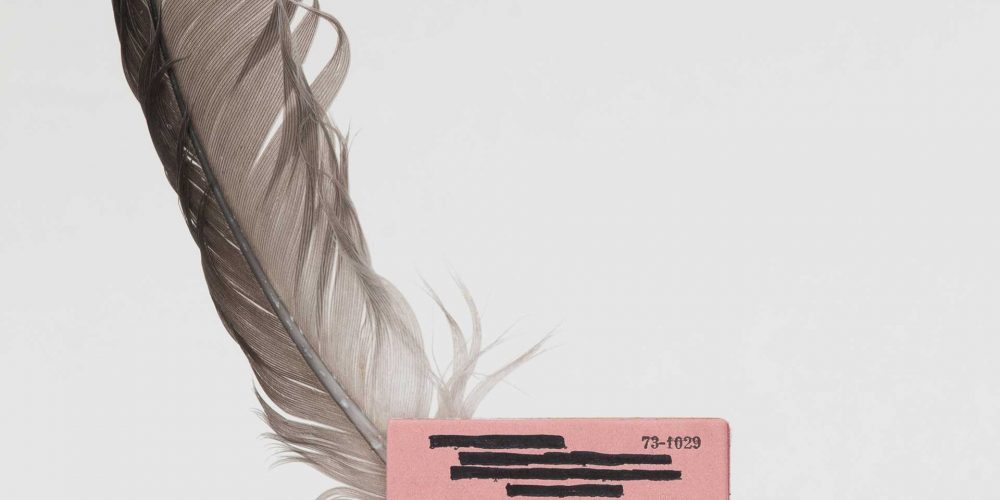

Schrift-bildlich gesprochen

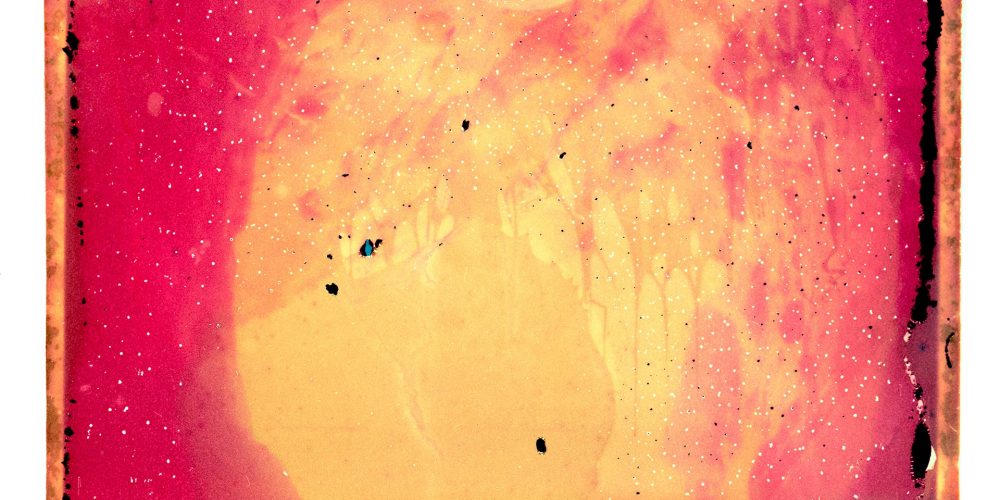

Nicht einmal zweihundert Jahre liegt die älteste Publikation aus der Dekade der jeweiligen literarischen Vor-Bilder unserer eben gekürten „Wort im Bild“ – GewinnerInnen zurück. Beachtenswerter aber als die zeitliche Konzentration auf exakt hundertsechzig Jahre erscheint die Auffälligkeit, dass damit alle zehn genannten Quellen in die gemeinsame Geschichte von Literatur und Fotografie eingebunden sind. Man wird zwar sehr wahrscheinlich zu weit gehen, der Erfindung und Verbreitung von fotografischer Technik und Wahrnehmung gleich eine direkte Beeinflussung der literarischen Sichtweise zuzusprechen und es scheint überaus schwierig, die Bedeutung der fotografischen Wirklichkeit (fotografische „Utopien“ lassen sich bis ins 1. nachchristliche Jahrhundert zurückverfolgen) für die Literatur und ihre Gestaltungsformen konkret festzulegen. Und doch dürften die aktuellen Licht-Schriften die Annahme des bestimmt „Photographischen“ ihrer je genannten Texthintergründe umso stärker bekräftigen. Dieser Eindruck erhärtet sich weiter aufgrund von Beschreibungen und Reflexionen der optischen Welterfahrung durch das „unbestechliche“ Lichtbild in den meisten der von den Fotografinnen und Fotografen ausgewählten Werke. Dazu ist festzustellen, dass sich unter den zehn Buchautoren auch einflussreiche Lichtbild-Theoretiker² befinden, die durch ihre feinsinnigen Analysen des fotografischen Wesens den Blick auf das technisch verwirklichte Bild maßgeblich schärften.

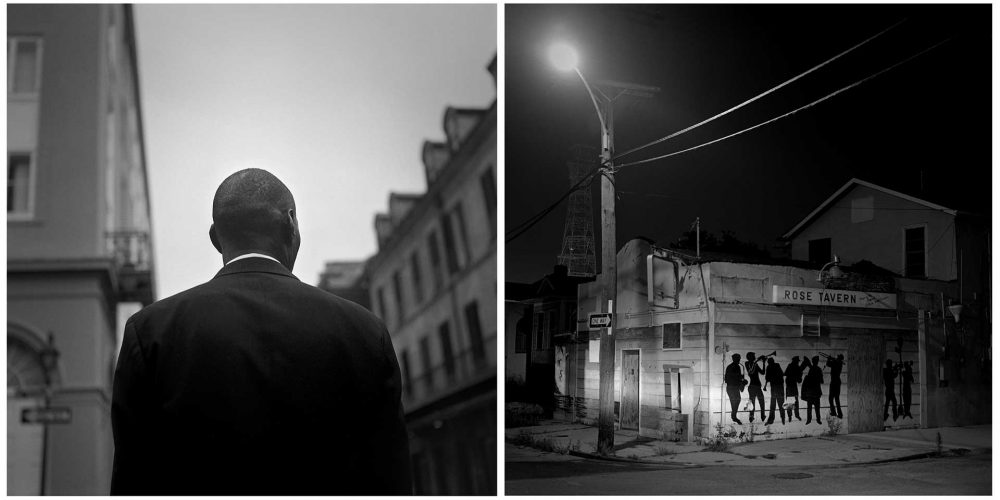

So scheinen die diesjährig prämierten fotografischen Über-Setzungen – eben auch vor dem Hintergrund der spezifischen Konstellation ihrer einzelnen literarischen Inspirationen – weitere anregende Möglichkeiten zu bieten, um den Fragen darüber, wie Literatur als Fotografie, wie Fotografie als Literatur gedacht werden kann, nachspüren zu können. Besonders heutzutage, inmitten einer alltäglichen, scheinbar oft gerade durch diese Alltäglichkeit unsichtbar werdenden visuellen Weltdarstellung, mag die in Anlehnung an den ungarisch-US-amerikanischen Maler und Fotografen Lâszlô Moholy-Nagy formulierte (Wieder)Begegnung mit Fotografie wohl ebenso wichtig sein wie die Begegnung mit Literatur. Gerade jetzt, in der Kultur von wort- und bildsprachlicher Selbstverständlichkeit, müsste die spätestens seit den ersten Anbahnungen fotografischer Realitäten bekannte Wahrnehmung, dass „Wort und Bild sich immerfort suchen“ (Goethe), wenigstens in schrift-bildlicher Hin-Sicht, als eine verbindende Kraft erachtet werden.

David Schuller

1Vgl. dazu die Verserzählung Capilli Flavi Earinis: “Die blonden Haare des Eranius”: …”Schaue nur fest hinein und lasse dein Bild für immer zurück. So sprach er und schloss den Spiegel, nachdem er so das Bild geraubt hatte.”

2 Zu erwähnen sind hier insbesondere Roland Barthes, Charles Baudelaire und Italo Calvino.

Literally-visually speaking

Not even two hundred years have gone by since the oldest publication from the decade of the respective literary pre-pictures of our recently selected „Wort im Bild“-Winners was first released. More noteworthy, however, than the conspicuous concentration of time over exactly one hundred and sixty years, appears to be the fact that all ten text-originals are thereby queued in the common history of literature and photography.

In fact, it is very likely that one goes too far when proclaiming an immediate influence by the invention and the dissemination of photographic techniques and perception on the literary view, and it still seems to be highly difficult to concretise the impact of photographic reality (photographic „Utopias“ can already be traced back until the 1. Century AD1) on literature an its formal structures. And yet, the latest light-writings seem to reinforce even more the assumption of the specific photographic of these textual backgrounds. This impression is further corroborated by the discovery of several references to the optical world experience through the „incorruptible“ image in almost all of the texts selected by the artists. In addition, the list of authors also includes theorists2, who carried out perceptive analyses of the photographic nature, which significantly sharpened the look at the technically realized image.

Therefore, this year’s photographic trans-lations of the award winning artists provide once again – also against the background in the specific constellation of the chosen literay inspiration – some stimulating opportunities to trace those questions such as how photography can be thought as literature and how literature can be thought as photography. Especially nowadays, in the midst of an everyday occurring visual world appearance that apparently through this everydayness more and more becomes invisible, the encounter with photography can – in the style of the hungarian-US-american painter and photograph Lâszlô Moholy-Nagy – reasonably be as important as the encounter with literature. Particularly now, in a culture of verbal and visual self-evidence, the perception, at the latest known after the first beginnings of photographic realities, that „word an image are always looking for one another“ (Goethe), ought to be regarded, at least in a literal-virtual per-spective, as a binding force.

David Schuller

1 Therefore refere to the epical narration of Capilli Flavi Earini “The blond Hairs of Eranius”: …”Just look firmly into it and leave your image behind forever. So he spoke and closed the mirror after stealing the picture.“

2 Particular mention should be made of Roland Barthes, Charles Baudelaire and Italo Calvino.